The Meditation Maze: How to Find a Practice That Actually Fits You (Part 1)

From mindfulness to mantras, not all paths lead to the same place. Here’s how to navigate the modern meditation landscape.

For all the years I’ve been teaching meditation, close to two decades now, there are two questions I get asked more than any others:

Am I doing it right?

And what type of meditation is right for me?

I could write for days about the first (maybe I will, or record a podcast soon). But today, I want to speak to the second.

The meditation landscape is bigger than it has ever been.

Back in my day (ok Grandpa), we didn’t have nearly the same menu of options. Or rather, we didn’t know we had them. Some styles have evolved in just a few years. Others have experienced a resurgence of interest.

As a new meditator today, you hear about all the promised benefits:

Reduction in stress, better emotional regulation, sharper focus and performance. Improved mental health outcomes for depression, PTSD, and anxiety. And then the grander claims: enlightenment, psychic ability, even manifestation.

Meditation can feel like a panacea for everything, and there is usually some scientific study somewhere that people use to back it up.

No wonder so many people are confused.

Where do you start? With what practice? For what reason? What does it all actually mean?

Today, I am going to try to break down some of the most popular meditation styles and traditions I have seen rise during my time practicing and teaching. This is not an exhaustive list. Lineages often have countless variations, like vipassanā within mindfulness, and subtle distinctions inside those. But it is a start. One that will hopefully give you enough context to choose a path that feels right for your own goals, whether they are health-related, mental, spiritual, or somewhere in between.

I’ll also offer my honest critique of each style. These are just my opinions, don’t come for me. I am no ultimate authority. But I do believe it’s important to put everything on the table so we can make informed choices for ourselves. Ultimately, the best meditation practice is the one you are willing to commit to over time.

Ideally, it is one that makes you healthier, happier, wiser, and, in some small way, a more compassionate and altruistic version of yourself. Not because it makes you feel special or inflates your ego, but because it challenges you, refines you, and reminds you of what truly matters.

As you read, consider:

Why do I want to meditate?

What am I looking for?

What is this practice actually training inside of me?

Do the students of these practices resonate with me?

Here’s what we will explore:

Secular Mindfulness

Buddhist Mindfulness (Theravāda, Mahāyāna, Vajrayāna)

Vipassanā (S.N. Goenka Tradition)

Transcendental Meditation (TM)

Joe Dispenza Meditation

Dzogchen (The Great Perfection)

Zazen (Zen Meditation)

Somatic and Trauma-Sensitive Meditation

Nondual Inquiry (Advaita Vedānta Inspired)

Loving-Kindness and Heart Practices1. Secular Mindfulness

1. Secular Mindfulness

What it is:

Secular mindfulness is arguably one of the most researched and practiced styles of meditation in the West.

It is a stripped-down adaptation of Buddhist meditation designed for clinical and corporate settings.

Popular through programs like Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), secular mindfulness reframes meditation as mental fitness or training.

Claims to help with:

Stress management, anxiety reduction, emotional regulation, improved cognitive flexibility.

Technique:

Focused attention (on breath, body, sounds) or open monitoring (awareness of arising phenomena without grasping), returning attention non-judgmentally when distracted.

Benefits:

Reduces anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms (JAMA Psychiatry, 2014).

Improves working memory and executive control (Zeidan et al., 2010).

Lowers cortisol and systemic inflammation.

Critique:

Secular mindfulness is palatable for the West because it emphasizes science over spirituality or dogma.

It was largely popularized by figures like Jon Kabat-Zinn, who adapted Buddhist principles into MBSR to make mindfulness accessible to clinical and secular audiences.

While it delivers genuine psychological benefits, it often amputates meditation from its original ethical and existential roots.

Today, it has been critiqued as "McMindfulness"a form of self-soothing sold to a stressed-out population, enabling them to tolerate harmful systems without questioning them (Ronald Purser, The Guardian).

The risk is that mindfulness becomes just another performance-enhancing tool, rather than a means of seeing our lives more clearly and cultivating deep personal or societal transformation.

Practiced superficially, it can lead to emotional numbing, mistaking calmness for clarity, and resignation for wisdom.

In other words, it can help us sleep better and feel good, but not necessarily break through the deeper patterns that keep us stuck.

2. Buddhist Mindfulness (Theravāda, Mahāyāna, Vajrayāna)

What it is:

In Buddhist traditions, dating back over 2,500 years, mindfulness is part of a larger path toward freedom from suffering. It’s not taught as a standalone technique, but as one element of the Noble Eightfold Path: A way of living that includes ethical conduct, mental discipline, and the cultivation of wisdom.

At its core, Buddhist mindfulness strengthens one’s ability to stay present and aware of their direct experience. It prepares the mind for deeper insights into the nature of their reality, leading to the gradual unraveling of patterns like clinging, aversion, and identity that keep us caught in cycles of stress and dissatisfaction.

Claims to help with:

Liberation from suffering

Insight into impermanence, non-self, and the nature of compassion beyond self-interest

Technique:

The practice usually begins by anchoring attention to something immediate and neutral, like the breath or bodily sensations, while maintaining a broader awareness of thoughts, emotions, and perceptions as they come and go.

The difference between Buddhist mindfulness and secular mindfulness is crucial:

In secular mindfulness, you practice primarily to feel better, to reduce stress, improve focus, sleep better, and regulate emotions.

In Buddhist mindfulness, you practice to see through the illusions that cause suffering itself, aiming not just for symptom relief but for real freedom.

Through repeated practice, this form of mindfulness helps the student directly see three universal truths: that everything is always changing (impermanence), that clinging to experiences never brings lasting satisfaction (unsatisfactoriness), and that there is no fixed, permanent self at the center of our experience (non-self).

Rather than chasing pleasant states or optimizing performance, Buddhist mindfulness leads to a paradigm shift in how we relate to life itself, loosening the grip of craving, fear, and false identity that lie at the root of suffering.

Across all Buddhist schools, the goal is not to stop thoughts or reach blissful states, but to cultivate a stable, honest seeing of reality as it is, without distortion.

Benefits:

Builds concentration, focus, and compassion

Decreases fear of death and rigid identity attachment

Strengthens altruistic behavior and reduces in-group bias

Shrinks activity in the default mode network linked to self-referential thinking (Brewer et al., 2011)

Critique:

Buddhist mindfulness is fucking hard. And it requires effort, dedication, and a willingness to confront impermanence, suffering, and the instability of the self, a reality most people in the west would rather avoid.

It also asks for trust in the Dharma, the broader Buddhist framework for living that includes ethics, wisdom, and ‘right’ action. This religious or philosophical dimension can be confronting for those who want meditation without any deeper system of belief.

Although it is possible to practice Buddhist mindfulness in a secular way, understanding the context it was born from provides important framework.

The depth of self-inquiry it requires can be destabilizing, especially for those not psychologically prepared to examine their mind and its tendencies.

Without proper support and guidance, key insights can be misunderstood, hardening into apathy, emotional rigidity, or philosophical confusion.

Buddhist mindfulness is ultimately a confronting practice. I may be slightly biased as it’s the one that I fell into and come back to over and over again. But it has its obvious challenges. It does not just soothe the mind or make you feel good, at a the beginning; it can tear down your illusions of self, and invite you to question your work, your relationships, your purpose, everything you once thought was solid. That shit can f*ck you up.

3. Vipassanā (S.N. Goenka Tradition)

What it is:

Vipassanā, meaning "insight," was taught by S.N. Goenka, who learned it through the Burmese lay meditation tradition under Sayagyi U Ba Khin.

Goenka came to the practice seeking relief from debilitating migraines, and through observing bodily sensations with equanimity, realized that suffering stemmed less from pain itself and more from the mind’s reaction to it.

Goenka’s vipassanā is taught through intensive 10-day silent retreats, where students systematically learn to observe the arising and passing of sensations to realize impermanence directly.

Courses are offered worldwide on a donation basis (dāna), taught by volunteers who have completed previous courses.

Claims to help with:

Ending reactive patterns, building equanimity, experiential realization of impermanence.

Technique:

Systematic body scanning, observing sensations neutrally, without craving or aversion.

Benefits:

Increases emotional resilience and patience.

Strengthens interoceptive awareness and emotional regulation.

Reduces impulsive reactivity.

Critique:

Vipassanā builds extraordinary mental toughness. Many practitioners who stay with it develop enviable stability of mind.

However, for some, it can harden into an achievement-driven approach, where liberation becomes another thing to chase.

Modern wellness culture sometimes romanticizes Vipassanā retreats as detox experiences, stripping them of their existential seriousness.

There are also real risks. Intensive retreats can unearth deep, unprocessed emotional material without adequate support, leading to dissociation, panic, or despair.

Still, I have deep respect for the tradition and its commitment to accessibility and integrity.

4. Transcendental Meditation (TM)

What it is:

Transcendental Meditation (TM) sometimes known as Vedic meditation was developed by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in the 1950s, drawing from the ancient Vedic traditions of mantra and meditative absorption.

While rooted in spiritual ideas, TM was reframed as a "science of creative intelligence" to make it accessible to the Western world.

It uses a mantra-based method where the student silently repeats a personalized bija mantra (seed sound), allowing the mind to settle into quieter states of restful awareness. There’s a heavy emphasis on letting go, surrender and relaxation.

Claims to help with:

Stress reduction, increased creativity, deeper emotional balance.

Technique:

Silent repetition of a personalized mantra for 15–20 minutes twice daily.

Benefits:

Reduces blood pressure and cardiovascular risk (American Heart Association, 2013).

Enhances alpha brainwave coherence.

Decreases cortisol and improves mood regulation.

Critique:

TM excels at calming the nervous system without requiring confrontation with painful emotions or deeper conditioning.

It steers the student towards blissful states rather than wrestling with the discomfort of thoughts, sounds and sensations.

However, it leaves intact the underlying structures of craving, aversion, and self-identity.

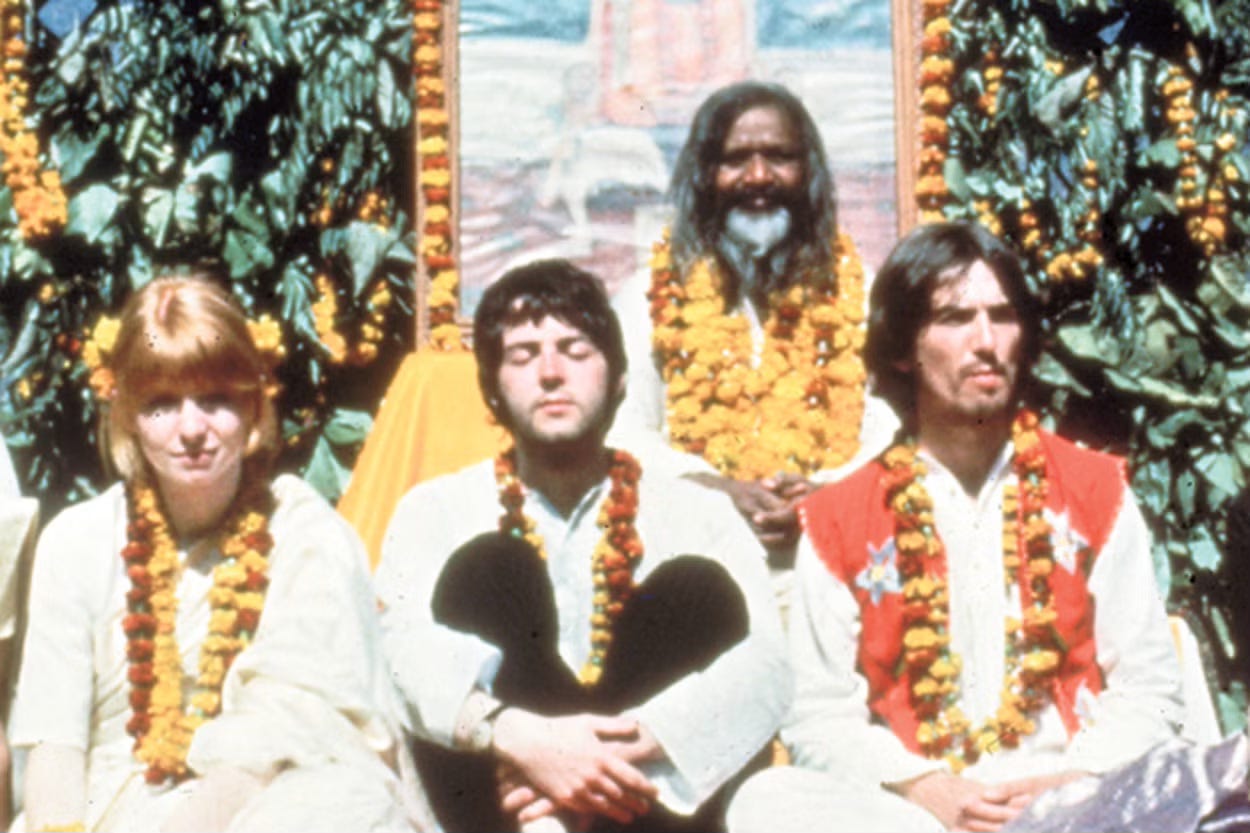

TM has also been criticized for commercialization, with high fees ($1,500–3,000) charged for receiving a personal mantra, and a heavy reliance on celebrity endorsements (The Beatles, Mia Farrow, David Lynch).

The practice has merit, and clearly helps many people.

But after learning the technique, I found that while it offered moments of restfulness, it did not offer a framework for how to live, love, work, or engage with suffering.

The risk is mistaking transient peaceful states for genuine transformation.

Next up: Part 2 — A look at the more unconventional meditation practices: from Joe Dispenza to Dzogchen to trauma-sensitive approaches. Some help. Some harm. Some ask everything of you. See you Wednesday.

Thank you Manoj for this very interesting article. I’m French, and here meditation techniques are not really popular. I work with a method called sophrology—do you know it? I’d like to offer sessions in English because I get the sense that it’s not very well known in the United States, and just like meditation, it can be truly transformative!